Why Morality, Law, and Ethics are Dead without God

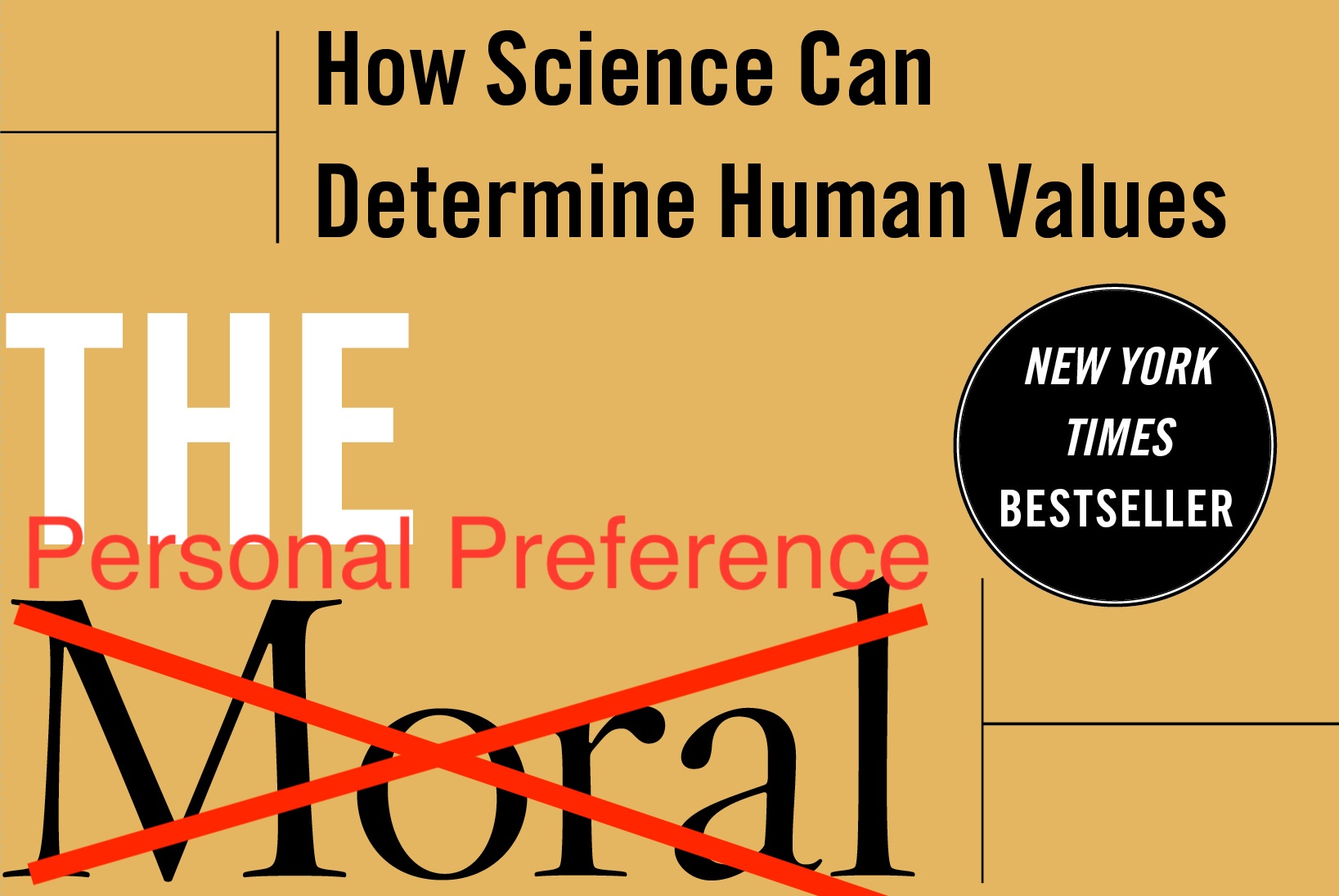

Sam Harris's new book, "The Moral Landscape," tries to merge science and human values, yet this circular reasoning only brings about more confusion and inevitably back to an external foundation in God.

Sam Harris's new book, "The Moral Landscape," tries to merge science and human values, yet this circular reasoning only brings about more confusion and inevitably back to an external foundation in God.

Morality, ethics, law, and religious beliefs have a dynamic and interconnected relationship. Although foundationally similar and related, there are differences of which characterize each term dependent upon situational relevance and subjectivity, despite each being objective in nature1. Analysis of the similarities, differences, and general as well as specific implications of these terms are reviewed to determine how morality, ethics, and law are related. A differentiation between two kinds of law, secular and religious, is required for a firm understanding between the two. Secular law, and its origin, emerges from social connections among equally fallible individuals and applies to each equivocally, while religious law is rooted in the inequality between man and God, with mankind subject to God’s transcendent nature2.

The term ethics comes from the Greek “ethos,” which describes a person’s character, a culture, or a habit of which is good3. Ethics is the scientific study of human behavior, the obligatory duties to one’s external environment, and the problematic nature of which involves every being. Ethics is said to occur due to the focus on mutually accepted common goods and conditions of foundational assumptions in which each culture relies upon to operate with one another4. Morality, on the other hand, stems from the maximization of human utility, from such, “doing the right thing” is judged5. Without an objective, inherent, and external standard of individual morality, ethics and law are merely preferences of which cannot, and should not, be enforced upon others.

Morality, Law, and Ethics

In many ways, a society’s laws systemize the norms, customs, and moral values of which grow and evolve as social awareness and what is seen as “right” and “wrong” is discovered1. In civil law, societal members are responsible for what is reasonably and liberally willed, a responsibility of foreseeable actions and their effects as being evil or harmful. This responsibility is shared with ethics, as organizations and common cultures seek to pursue “what should be” in the social nature of environments with compulsion, implemented at all organizational levels with transparency, consistency, and equality3. Both laws and ethics rely on human reason to determine appropriate action, while morals can be found to provide the foundation of the law as the broad societal conception reflected in legal obligation1. Since moral and ethical concepts are objective, long-lasting effects of prosperous human engagement, not determined by purely sentimental, momentary determination, they are fashioned into law in every aspect of a society’s governing system.

Moral Standards for Law

Societal law should change to reflect society’s discovery of improved moral standards1. Laws and ethics, which regard liability of moral responsibility within legal systems, are comparable with one another and differ in scope of use. Indifference to another person’s life is morally wrong and therefore legally wrong in what is known as “legality of negligence” by preventing a third-party from helping another individual, ignoring the inherent value of another’s life. Ethics, in its attempt to create a social atmosphere of the highest moral value, is the basis of which laws reflect moral accountability and cultural responsibility.

If people are given value by God, who is an external standard and foundation of value, then moral wrongs and ethical duties can be legally enforced, yet by what standard is value given to a human if there is nothing outside the physical here and now? How can people have more moral value than chickens, rodents, or a clump of cells within a body, or even on the side of a road, if each are made up of the same components and are merely products of time and chance? The question is begged as to whether all life has value or none of it does, and if it all has value, then why? Read more here.

In summation, collective responsibility is the driving force in law and ethics, each founded on the moral value of the individual within the collective, as law and morality are both concerned with practical reasoning, such as what to do, the aims of life, and who to be as an individual6. Both law and morality involve what is good, right, or virtuous, each expressing value judgements. As well, these concepts are used to distinguish and judge between reasonings in society’s social encounters.

Morality as a Building Block

Ethics are found to be eternal, transcendent, divinely inspired ideas and virtues, while morality is a temporal, spatially conformed, rule-based and limited application of ethics, with morality translating ethics into space and time3. Ethics is the theory while morality is its practice. Within ethics lies two forms of existence, one social and the other individual (Boldizar & Kohonen, 1999). The social form of ethics, as in moral philosophy, is the study of the manifestations of social values and norms of which are presented through morality and law and can be found in the forms of collective guidelines, codes, and canons. The second, individualistic form of ethics, is the foundation of which the social theory of morality and law is built upon, and without which, ethics can only be speculative.

Morality within society can be found separate from law in the institutional backing of such laws having social frameworks built to normalize and conform them, while morals have no such socialization6. Ethics as well lacks society-wide institutionalization for its presence, yet it does share a commonality with law in its foundation within every organization’s practice, physically found through codes of conduct. Morality, although found to be the foundation of laws and ethics, is not specifically built into the system as tangibly as laws and ethics. Instead, it is seen as the objective standard used to formulate the impartial nature of laws and ethics and the values they impose on their cultures. Morality is the building block of one’s individual sense on “what is good” and “right,” while ethics and law, whether secular or religious, support, guide, and enforce societal groups towards socially applicable standards found within morals. The specific difference between morality and law is morality’s role in revealing the ultimate standards of which human conduct is assessed.

Atheists, Naturalists, and Richard Dawkins

Through narrative transference during discourse of individual histoires—what one believes has happened previously, is happening now, and will happen in the future, conversation brings unity between subjects of discussion, and as such, allows both parties responsibility of interpretation of such narrative2. Through this discourse, human culture, what Freud believes is the critical substance of mankind’s nature, manifests common reality, including law and religion. Within these co-constructed realities, authentic human relationships begin and are sustained by commandments. If such commandments are given through a divine, perfectly good and all-knowing being, sustainable morality, its ethical implications, and the laws built upon them, can be justified, followed, and administered with force and universal acceptance. With this view, laws are found to make the society of which they reign—lex facit regum, instead of society making such laws. Without an external, unchanging, objective standard of which morality comes, such as those given through religious law through divine command theory, society can only provide majority preferences of which laws and ethics must subject themselves towards2.

If society deems what is appropriate, based on personal preference and not divine commandment and foundational sustenance, then is it fair to punish people for being who they were naturally, evolutionally pre-determined to become? Do people even have free will if there is no God? If the natural-materialist viewpoint is true, then people are merely reacting to the chemicals firing within their brains, no different than a soda can fizzing as the top is popped. How can a person be punished if the life they live now is merely a reaction to the compilation of what they have encountered, of what their environments have produced them to be, as their free-will is merely an illusion to the truth of what can be known as an evolutionary by-product? Richard Dawkins, one of the world’s most predominant atheists and a professor of taxonomy at Oxford University, says in one interview that,

Presuppositional Inconsistencies

Atheists like Dawkins reject Darwinian morality when it comes to living life, yet they propose Darwinian evolution as a worldview. If a person has a worldview but does not live out the presuppositions of such worldview, then one would consider that individual either inconsistent in their beliefs or unable to accept the ramifications of such belief. This “survival of the fittest” ethics is said to be “ruthless” by Dawkins in one interview as well saying,

This is an interesting statement by a man who believes in no god, as he introduces his own moral code to follow, despite believing in no morality. One may object and say evolution can explain morality but one must dive into such argument to find the illogical conclusions, the circular reasoning used, and the foundation of God stolen from theists to make such claim.

Dawkins states,

Yet, he believes morality exists through evolution to allow us to engage together rationally.

Fallacies Revealed

There are six problems with this statement, as famous apologist Dr. Frank Turek points out:

- The first of which is the category fallacy, explaining moral laws by biological processes, two separate categories or more generally, using a descriptive versus prescriptive approach.

- The second is that biological processes in no way can show something to be “right,” morally just, or good. Biology itself merely shows what survives, not what ought to do so. This has horrible moral implications when one considers an extrapolation of such morality. If raping someone or murdering people provides a greater survival rate, then this would be an evolutionary advance and moral duty to be done. This logical progression of atheist thought makes popular atheist Sam Harris also accept anti-Darwinian morality as well, as seen by his debate with apologist William Lane Craig.

- A third point is that survival of the fittest is not the highest value in our society, altruism, the sacrifice of one’s self, is the highest value.

- As well, evolution involves change, constant change, and thus morality must change. If morality changes, then there is a potential for rape and murder to be morally good, just, and obligatory, and thus morality cannot be objective and unchanging.

- Evolution as an objective morality is more of a social contract that requires an objective morality to appeal to outside of itself. If someone breaks the contract, is it immoral to do so, and if so, who does one appeal to for such standard of immorality?

- Finally, the claim of survival out of cooperation is a pragmatic argument, not a moral one, a claim which is in actuality untrue in itself. Stalin, Hitler, and many other criminals all prosper, and do so well, because they do not cooperate with others. Dictators like those mentioned viewed life as Godless and thus moral law was seen as evolutionary by-product, requiring a duty to the human race to increase evolution’s work, a moral duty, and thus genocide is not only normal but inherent in survival—read more on evolution causing WWI and WWII and the deaths of hundreds of millions throughout the 20thcentury.

No matter one’s worldview, to establish morals as objective, God is required.

A Changing Morality is No Morality

Ethics must be grounded in philosophical anthropology, the theory of human nature, as Freud and Aristotle both agree, ethics cannot be formulated through scientific precision2. Godless morality, as Freud states, loses its unchanging nature and rigidity and its reliability on reason, thus having little effect against passionate impulses. If morality is built by people who are as fallible as those who commits such fallacies and is changeable by means of other fallible individuals, what value does it have in determining law or codes of ethics? As the state of mankind is ever-changing, especially in a world dominated by evolutionary ethics and science, subjective relativism, and an ever-expanding melting-pot of diversity, how can any individual be required to follow such doctrines when they are subjective and relative to those in charge and aligned current cultural popularity? Without an objective, inherent, and external standard of individual morality, understanding what is true and good for people and society cannot be ascertained3.

Morality, Law, and Ethics are Not Dead

Culture itself is the way in which people develop their nature within their environments, yet these environments, nature and the universe of which it exists, reflect an objective, innately predictable existence.

Although society tries to implement its own view of ethics and morality, humans have an objective, externally bestowed value of which cannot be created through legal systems and institutions but are instead the foundations of which these systems and institutions are built upon.

Without this innate, intrinsic moral worth, conferred externally by a divine creator, there can be no forcible right by members of society to impose ethical preferences onto others. Without an objective standard of moral perfection, people are merely dancing to their DNA, not responsible for acting on their own individually subjective morals. There must be something greater than society, of which society is built, for law and ethics to claim their power and rationality for force.

References

1 McGowan, R. J., & Buttrick, H. G. (2015). Moral responsibility and legal liability, or, ethics drives the law. Journal of Learning in Higher Education, 11(2), 9-13.

2 Novak. D. (2016). On Freud’s theory of law and religion. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 48, 24–34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2016.06.007

3 Hromei, A. S., & Voinea, M. M. (2013). Accounting between law, ethics and morality. SEA – Practical Application of Science, 2(2), 131-136.

4 Elfenbein, C. (2016). Debating the common good: Islam, modernity, and the ethics of cross-cultural analysis. The Muslim World, 106(4), 671-695.

5 Hodgson, G. M. (2014). The evolution of morality and the end of economic man. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 24(1), 83-106.

6 Cane, P. (2012). Morality, law and conflicting reasons for action. The Cambridge Law Journal, 71(1), 59-85.

7 Turek, F. (2014). Stealing from God: Why Atheists Need God to Make Their Case. Tyndale House Publishers, Inc.